The banking trojan known as Mispadu now targets users in Italy, Poland, and Sweden in addition to Latin America (LATAM) and Spanish-speaking people.

According to Morphisec, the campaign’s targets include businesses in the banking, services, automotive manufacturing, legal, and commercial sectors.

According to a report released last week by security expert Arnold Osipov, “Mexico remains the primary target despite the geographic expansion.”

“Thousands of credentials have been taken as a result of the attack, with records going back to April 2023. The threat actor uses these credentials to plan harmful phishing emails, which puts the victims at serious risk.”

Mispadu, also known as URSA, gained notoriety in 2019 when it was seen using phoney pop-up windows to steal credentials from financial institutions in Mexico and Brazil. In addition, the malware with a Delphi base can record keystrokes and take screenshots.

Recent attack chains, which are usually disseminated through spam emails, have taken use of a Windows SmartScreen security bypass issue (CVE-2023-36025, CVSS score: 8.8) that has been patched to compromise users in Mexico.

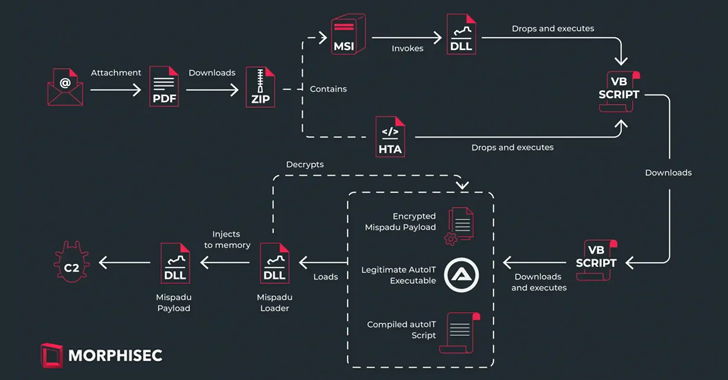

The infection sequence Morphisec analysed is a multi-step procedure that starts with a PDF attachment included in emails with an invoice theme. When the file is viewed, the receiver is prompted to click on a malicious link to download the entire invoice, which downloads as a ZIP package.

Either an MSI installer or an HTA script is included in the ZIP file, and these are in charge of downloading and running a Visual Basic Script (VBScript) from a remote server. A loader is then used to decrypt and inject the payload—the Mispadu payload—into memory. All of this is done by downloading and launching a second VBScript through an AutoIT script.

“This [second] script is heavily obfuscated and employs the same decryption algorithm as mentioned in the DLL,” Osipov stated.

“Before downloading and invoking the next stage, the script conducts several Anti-VM checks, including querying the computer’s model, manufacturer, and BIOS version, and comparing them to those associated with virtual machines.”

The use of two separate command-and-control (C2) servers—one for retrieving the intermediate and final-stage payloads and another for exfiltrating the credentials that were obtained from more than 200 services—is another characteristic of the Mispadu attacks. At present, the server contains over 60,000 files.

This development coincides with the DFIR Report’s description of an intrusion that occurred in February 2023 and involved the use of malicious Microsoft OneNote files to distribute IcedID, which was then used to dump the Nokoyawa ransomware, Cobalt Strike, and AnyDesk.

Exactly a year ago, Microsoft declared that it will begin preventing 120 extensions from being used maliciously within OneNote files.

YouTube Videos for Game Cracks Serve Malware

The information is also related to the fact that, according to enterprise security company Proofpoint, a number of YouTube channels that support unlicensed and cracked video games are using malicious links in their descriptions to spread information thieves like Lumma Stealer, Stealc, and Vidar.

Security researcher Isaac Shaughnessy stated in a report released today that “the videos purport to show an end user how to do things like download software or upgrade video games for free, but the link in the video descriptions leads to malware.”

While there’s evidence that these videos originate from compromised accounts, it’s also possible that the threat actors behind the operation set up temporary accounts in order to spread their messages.

Discord and MediaFire URLs that link to password-protected archives and, eventually, the installation of the stealer malware are included in every video.

According to Proofpoint, it has discovered many unique activity clusters that spread stealers on YouTube in an effort to target non-enterprise users. A specific threat actor or organisation has not been identified as the source of the campaign.

“The techniques used are similar, however, including the use of video descriptions to host URLs leading to malicious payloads and providing instructions on disabling antivirus, and using similar file sizes with bloating to attempt to bypass detections,” added Shaughnessy.